In the nineteenth century, the world’s gaze turned to Africa for its wealth of resources. Sudan felt the immense effects of colonialism beginning in 1821 with the Turco-Egyptian invasion. However, it was the Anglo-Egyptian condominium rule that left the biggest imprint on Sudanese culture and exacerbated the tensions between the northern and southern regions.

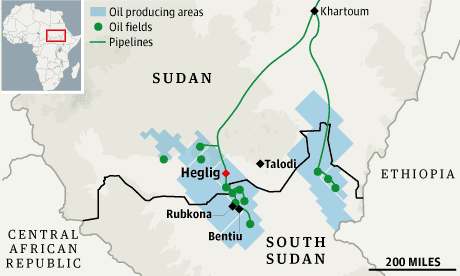

As a result of Turkish influence, Islam had taken a hold, though hardly a centralized one, in the northern part of the Sudan, while southern Sudan would remain neither Islamicized nor Christianized until the mid 20th century (Barnard). Great Britain hoped to capitalize on the country’s wealth of resources (the Nile River and oil) as well as the already booming slave trade operations run out of northern Sudan. Through this system, northern Sudanese captured and exported southern Sudanese to the new world. When Great Britain halted these operations, the region’s most lucrative source of revenue, uprisings ensued. To regain control, Great Britain established a joint authority rule with Egypt, though the British had significantly more power over the region. This British colonization, masqueraded as equal rule with Egypt, was largely positive for the northern Sudanese. The British granted them political and administrative control, put leaders of Muslim sects in control, and provided assistance in building infrastructure and education. This developmental assistance from the British in northern Sudan prepared the country for eminent independence and authority over the southern region.

What is now South Sudan remained largely tribal and indigenous until colonization. The cultural traditions of the region and the influence of neighboring countries such as Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya, hardly meshed well with the changes that came with colonization. Rule from its northern counterpart left a sour taste in the mouths of the south Sudanese, who had no experience with formal government, much less one that ran their region as a slave trade business venture and enforced policy that strongly deviated from tradition. The British ordered missionaries into southern Sudan in 1898 and ordered a halt to Islamic missionary work (Breidlid). They later went a step further, making English the official language and discouraging the use of Arabic. The British tried to incorporate tribal and indigenous practices into their control of the region with the “Native Administration” policy. This idea relied on tribal chiefs within southern Sudan to administer local law. Though indigenous leaders now had power, this sort of hybrid, indirect government made a mockery of tribal rule, for chiefs were made to uphold laws imposed by the British rather than the values of their communities.

It is through this indirect rule that the northern and southern regions of Sudan became increasingly polarized. The goal of Native Administration Policy (indirect rule policy) was to “build up a series of self-contained tribal units with structure and organization based upon indigenous customs, traditional usage and beliefs” (Heleta). However, it became so cumbersome to integrate colonial control into tribal and traditional practices that Great Britain eventually resorted to a minimalist approach to colonial activity in the region, withdrawing their influence in a way that equated to neglect. The regions were essentially sealed off from one another with the 1922 Passports and Permits Ordinance which removed all northern administers, revoked northern trader licenses, and required permits for northerners to travel to southern Sudan.

Leave a comment